Model Totem Poles: Tradition and Transformation

Waddington's Blog | August 27, 2022

Categories: news

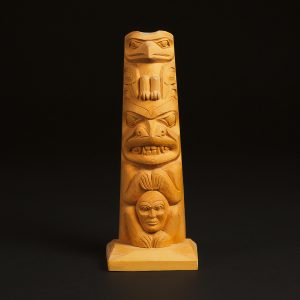

In the latter portion of the 19th century, a small number of First Nations artists in the middle and northern Northwest coast of North America began carving diminutively sized model totem poles for sale and trade to Euro-Canadian and American visitors to the region. The form of the model poles was derived from monumental counterparts whose origins predated European contact. Large carved poles proliferated in the early 19th century. Couched in the aesthetically complex and sophisticated language of transformational formline imagery, they gave material form to the mythology of the people who sculpted them, proclaimed the rights of their owners, memorialized them in death, and demarcated the territory in which they lived.

Although the first known model totem poles were sculpted in the 1880s, culturally the exchange of sculptural objects by First Nations coastal peoples emerged from a long and active tradition of coastal and inland trade that was essential to the regions’ economies in the time predating European contact. In the latter years of the 19th century totem pole carving, both monumental and model, quickly expanded into the southern reaches of the coast, and since, beyond. The image of the totem pole has almost certainly become the most popular and well-known signifier of the Northwest Coast and its peoples, and the early poles themselves have become in their monumentality, image dense figuration, and aesthetic clarity, objects of the utmost aesthetic veneration.

Made primarily for sale to outsiders, the appreciation of model totem poles has long suffered from a limiting conception of the form as “tourist art”. The descriptor, while applicable to their origin, has come under increasing criticism for its exclusion of the complex and diverse motivations of the artists who create them and of their viewing public, as well as the aesthetic mastery of the artists who have worked in the medium.

As the importance, and breadth of variation in model totem poles has increasingly been appreciated, structures to help us understand their cultural and aesthetic significance have emerged. A framework useful to both scholars and collectors assembled by Micheal D. Hall and Pat Glascock is outlined in the text documenting the landmark 2010 exhibit Carvings and Commerce: Model Totem Poles 1880 – 2010. The authors divide the history of the medium into four temporal periods outlined below.

EMERGENT PHASE: 1880 – 1910

Made for trade to early Euro-America and Canadian visitors to the coast, they are formally characterized by their iconographic complexity, sculptural harmony, and absence of painted embellishments, or minimal painting.

Emergent phase model totem poles are sometimes sculpted in wood but more often are carved from the black carbonaceous shale unique to Haida Gwaii (Queen Charlotte Islands). They are primarily associated with Haida artists, although early wooden examples have also been associated with Tlingit and Kwakwaka’wakw makers.

Many works of this era are unsigned and so identification of authorship is primarily based on stylistic attributions to works with documented makers.

DYNAMIC PHASE: 1910 – 1940

Dynamic Phase model totem poles exhibit brighter colours then their Emergent Phase forbearers, and sometimes feature stylistic characteristics more representative of individual style. Southern artists discovered Northern styles and began to develop their own form language.

External government and missionary forces during this period increasingly attempted to restrict and restrain traditional life ways of First Nations coastal peoples.

It has been suggested that model totem pole produced during this era served in part as a subversive response by their makers which helped to sustain Indigenous identities. Perhaps counterintuitively, this period was accompanied by an increasing market for traditionally informed Indigenous art and crafts in which consumers responded positively to individualism and pride of authorship. Works of this era are often signed by the artists.

COSMOPOLITAN PHASE: 1940 -1970

Totem pole restoration projects in Canada and the United States by universities and museums spread public interest in totem poles. Exceptional model totem poles by Indigenous artists of this period were often made by second and even third generation descendants of Dynamic Phase masters.

The Kwakwaka’wakw artist Ellen Need was the granddaughter of legendary model totem pole carver Charlie James. Wilson and Ray Williams were sons of the important Dynamic Phase Nuu-Chah-Nulth maker Sam Williams.

Addressing a new market demand unfettered by earlier expectations of “authenticity” from buyers, makers in the 1940s and 50s often painted their poles in flamboyant colours, sometimes carving in playful and further divergent creative styles.

ANALYTIC PHASE: 1970 – 2010

Many Indigenous artists were rediscovering and sometimes reinterpreting past traditions and earlier aesthetic approaches. Books on elements of Northwest coast style, most notably by scholar and artist Bill Holm, attempted to systematize and explain the foundational structure of 19th century Northwest Coast designs.

Artists moved freely between regional styles and began to develop full time careers as artists. Exceptionally refined and diverse artist practises flourished.

ABOUT THE AUCTION

Offered online August 27-September 1, this auction features an expansive collection of model totem poles from 19th and 20th century Northwest Coast artists working in the medium, including a remarkable array of the notable artistic visions associated with the subject over the past 100 years.

We invite you to engage with artworks by these foundational and important artists whose work has embraced both tradition and transformation.

View the gallery online and visit us at our public previews, which are available:

Sunday, August 28 from noon to 4 pm ET; Monday, August 29 from 10 am to 7 pm ET, and by appointment.

Contact us for more information.