by Palmer Jarvis

By some estimates people have inhabited sites in the North American Arctic for over 3,000 years, but very little is known about the varied earliest inhabitants of the land. It is perhaps surprising given the harshness of the climate that a wealth of material culture has survived them. Preserved in the permafrost amidst organic matter and the invading minerals which have over centuries given their surfaces an often-dark mottled colouration, many ancient Arctic objects no longer sport the gleaming white surfaces that would have been known to their makers.

Changes in appearances acknowledged, the aesthetic statements made in objects by Paleo and early Historic makers are undiminished in their importance, often one of the most telling records of their lives. Looking at and handling the objects that they created tells us something about the object environment in which they worked and lived, and gives tangible form to their relationships with animals, fellow humans, and the cosmology that they understood to undergird both. Lastly, the outlooks expressed in these material records suggest challenges to our perspectives on early Arctic peoples, and perhaps our own broader relationship with objects. This is to say nothing of the rewards of our direct emotional experience of the forms that these artists so adeptly sculpted.

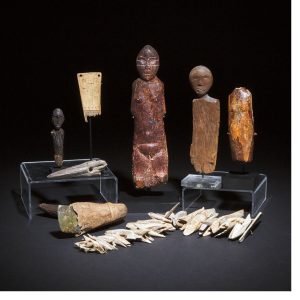

Objects made by circumpolar peoples have for the vast bulk of their history been small. Old Bering Sea (OBS) cultures in the Western Arctic, their later Punuk and Thule descendants, as well as individuals in Ipiutak, and Dorset cultures, or later Inupiat, Yupik, and Inuit descendants, have to varying degrees traditionally been nomadic, requiring objects to be highly portable. Add to this, infrequent supplies of wood, and material resources largely restricted to the limited spatial confines of ivory and bone, and what developed was a material culture on a restrained scale. Collectors of 20th century Inuit Art will be well aware of the longevity of this inclination, as many of the earliest, and some later masterpieces of modern Inuit sculpture are of a size that may have appeared surprisingly small on first encounter. The limited size of many objects by Indigenous Arctic makers has encouraged a density of detail that rewards close inspection, and delights upon the intimate encounter. Tools and other objects of utility are paired down to the essential encouraging a functional elegance that may to a Euro viewer be evocative of masterworks or early 20th modernist design.

Figural sculpture representing human or humanoid figures is often occurrent among surviving OBS objects, appears with some frequency in many paleo cultures, and was made in abundance by later Inupiat and Yupik artists. Features on many Paleo and Historic figures share some related elements which can include distorted facial features, implied skeletal marks, and the presence of tattoo patterns, elements considered suggestive of the supernatural in the earliest contextually documented instances. Objects with more readily distinguishable utilitarian purposes such as harpoon heads, combs, ulus, qulliqs (stone oil lamps) and so forth, have at various periods been subject to elaborate embellishment, or profound aesthetic restraint. While an OBS III harpoon headmay be embellished with nucleated ellipses thought to be eyes, a 19th century Eastern Inuit examplemade in the form of seal, and others againmade with elegant simplicity their defining characteristic, it has been suggested that these sometimes-disparate aesthetic decisions, typically conventionalized within a distinct culture and period, are a response to a shared challenge that follows from an understanding the of trans-Arctic notion of Inua.

Inua in short is an animistic notion of the universe in which all living beings, and even inanimate objects – but perhaps most significantly animals subject to being hunted – are conceived as imbued with a spirit representative of consciousness. This spirit or Inua is a foundational paradigm in North American Arctic conceptions of spiritual order as far back as can be documented, and is thought to dictate the varied designs of early Arctic implements. Within the Inua construct an individual was required to pay respect to, and his tools elicit pleasure in, an animal (or object’s) spirit since it was believed that the material manifestation would favour only those who observed the rituals dictated by their cosmology. Among many Western and central Arctic Inuit of the late 19thcentury down into the present it is sometimes believed that the Inua of an animal is reincarnated, bringing a dire long-term implication to the actions of a hunter who does not respect required protocols.

In a cosmology that necessitates beauty, the boundaries between the aesthetic and utilitarian are dissolved. It is perhaps this characteristic more than any other that unites the objects offered in Looking Backward and which invites us to indulge contemplative attention across the wide array of objects which it includes.

ABOUT THE AUCTION

Looking Backward: Archaic Arctic Art and Artifacts is online July 9 – 14.

Contact us to find out more.