Printmaking was introduced in the Arctic by James Houston, an artist and Government of Canada administrator. Tasked with exploring projects that might supplement the incomes of Inuit communities in the wake of the decline of the fur trade, Houston quickly recognized the potential of Inuit art. In 1957, Houston introduced artists at Kinngait (Cape Dorset) to printmaking techniques, setting up a studio with printing equipment. While the artform has little precedent in Inuit culture, it has been noted that “there are affinities with incised carvings on bone or antler, women’s facial tattoo marks, or inlay skin work on clothing, mitts and footwear.” Stone, bone, ivory, antler and wood can be found in the Arctic, but paper was nonexistent until its introduction by European explorers.

Houston travelled to Japan in 1958 to enhance his own skills, studying under the master printer Un’ichi Hiratsuka. He returned to the Arctic with new techniques and practices, which he in turn taught to local artists. The first prints were released to market in 1959. Their success led to the establishment of printing studios in Pangniqtuuq (Pangnirtung), Qamani’tuaq (Baker Lake), Povungnituk and Ulukhaktok (Holman). Print collections continue to be released annually in controlled editions. Early portfolios were issued in editions of 30, while today an edition of 50 is more common.

A NOMADIC CULTURE

Since their first contact with Europeans, the Inuit’s powers of perception and understanding of their surroundings has been remarked on. Writing in the 1950s, Edmund Carpenter observed that Inuit-drawn maps were astonishingly accurate when compared to maps made using aerial photographs. Acutely aware of their environment – one of the harshest on Earth – their language encompasses a wide range of words to describe various types of winds and snows. Carpenter noted that seals, birds, planes, boats and other changes in their surroundings were spotted by the Inuit long before he observed them, and that the Inuit possessed a remarkable ability to retain information, being quickly able to synthesize and reproduce what they have learned, be these new ideas, or skills, such as the ability to repair and reconstruct complex mechanical engines. Also remarkable about the Inuit was their ability to pass on information between generations without a written tradition – in short, a myriad of aptitudes well-honed by a nomadic culture.

This was this rich culture that Houston found himself working within. Like any great artistic moment, conditions needed to be fertile, and indeed they were in the 1950s. In a way, Houston simply provided a spark – very quickly, a culture which had not been exposed to books and Western art-making mediums was able to master their forms. Several of the greatest artists the Arctic had ever produced only came to make art later in life. Take for example Parr, who spent the first six decades of his life as a hunter before creating some of the most sought-after drawings in a short period of only a few years.

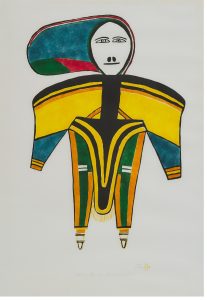

JESSIE OONARK

Like Parr, Jessie Oonark lived nomadically for the first 50 years of her life, involved in traditional pursuits such as processing and sewing animal hides to make clothing. In the 1950s, a decline in both caribou populations and the market for pelts caused a famine among her people. Oonark lost her husband and four of her twelve children to starvation. Along with hundreds of Inuit, Oonark and her family were relocated by the Canadian government to a permanent settlement in Qamani’tuaq (Baker Lake) in 1958. To support herself and her children, she worked various odd jobs including sewing, cooking and cleaning.

Oonark had never made drawings before moving to Baker Lake at the age of 52. Apparently, Oonark saw some illustrations made by children and proclaimed that she could do better herself, and picked up the tools to prove it. Dr. Andrew Macpherson, a visiting biologist, saw the resulting drawings, and gave Oonark more materials. Over the ensuing years, the two swapped art supplies for art. Self-taught, her work also attracted the notice of members in both the Qamani’tuaq and Kinngait (Cape Dorset) artistic communities, giving her the opportunity to work with printmakers in both settlements. This is especially notable given that she did not live in Kinngait, and was the first non-resident to be accorded the privilege.

Oonark was given a small studio and a stipend, allowing her to devote more of her time to creation. Wildly prolific and dedicated to her work, at times her output was around forty to fifty drawings per week, more than 100 of which were translated into prints for the annual Sanavik Cooperative Baker Lake Print Catalogue between 1970 and 1985. Her son, the artist William Noah, remembers her always working, at a loss to recall what his mother did for fun. He recalls that “there was always that determination to do every task to the very best of her abilities, and she told us we must do the same.”

Waddington’s is pleased to be offering Oonark’s “Woman” as lot 61 in our Prints & Multiples auction. We invite you to read more about Jessie Oonark and this work. Other Inuit printmakers featured include Kenojuak Ashevak, Mary Pudlat, Ningeokuluk Teevee, Ohotaq Mikkigak and Annago Ashevak.