Reclaiming Our Names

Jun 22, 2022

by Heather Campbell

In this extension of Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami President Natan Obed’s feature, Reclaiming Our Names, from our Fall 2020 issue on Relations, artist, archivist and arts administrator Heather Campbell—the IAF’s Strategic Initiatives Director—reflects on the often culturally insensitive descriptors of Inuit and other Indigenous peoples left behind in archival photographs, documents, maps and more, and identifies how she and other Indigenous researchers at Library and Archives Canada worked to make them better.

The We Are Here: Sharing Stories initiative was a special digitization project of Library and Archives Canada (LAC) that ran from September 2017 to November 2020. Three researchers of Indigenous descent, of which I was one [1], were hired to comb through collections that were thought to have a wealth of Indigenous-related material.

The main focus of our jobs was to identify and make changes to outdated and culturally insensitive titles, as well as to give greater context to the material.

Made up of photographs and other materials, most of the collections were donated by individuals, but some were created by the Canadian government. Some photos were titled by the photographer, but very often the title was assigned by the LAC archivist when they were processing the collection, either based on what was happening in the photo, or any information written in the album or on the back of the image for example.

Unfortunately, because most of these images are older, some of the terminology used is no longer appropriate. For these, we included an updated title in square brackets. During my time as the Inuit researcher at LAC, I came across some memorable images that sparked questions within me, our team, and the institution as a whole. Here are ten images that embody aspects of the collection, which I hope will spark equal curiousity in you.

Niviaqsarjuq—nicknamed “Hattie” (front and centre)—is the first woman that I identified as having tattoos in some images and no tattoos in others. She is the inspiration for my forthcoming blog about tattoos and identification on the Library and Archives Canada Discovery Blog. Niviaqsarjuq has been photographed by many visitors to the Arctic including J.E. Bernier, Geraldine Moodie, and George Comer. If you would like to see more images of Niviaqsarjuq (identified as Ooktook) I invite you to visit the Moodie collection at the Glenbow Art Museum.

According to the Mystic Seaport Museum, Nivisarnarq was known as the “companion” of George Comer during his travels and she was nicknamed “Shoofly”. In some images she has facial tattoos, and in others she does not. I suspect the lines were drawn on in most cases. Nivisarnarq’s relationship with Comer highlights the complicated role of women to visitors to Inuit Nunangat. Nivisarnarq is the great-grandmother of Bernadette Dean, who co-directed the 2009 documentary What Belongs to Inuit / Inuit Piqutingit with Zacharias Kunuk. In the film, a group of elders visit museums across North America to view Inuit cultural material, including Nivisarnarq’s amauti at the American Museum of Natural History.

This image of Mrs. Helen Konek went viral on social media through a Twitter post created by her grandson Jordan Konek in 2019. CBC Radio later interviewed her about becoming a social media sensation, and what it was like being photographed by Mr. Harrington. This photograph causes me to pause and think about photographic consent, and photographer/subject relationship. Were the people in photographs of this time aware of the implications of being photographed, or aware of how their images would be utilized by southerners or by their descendants in the future?

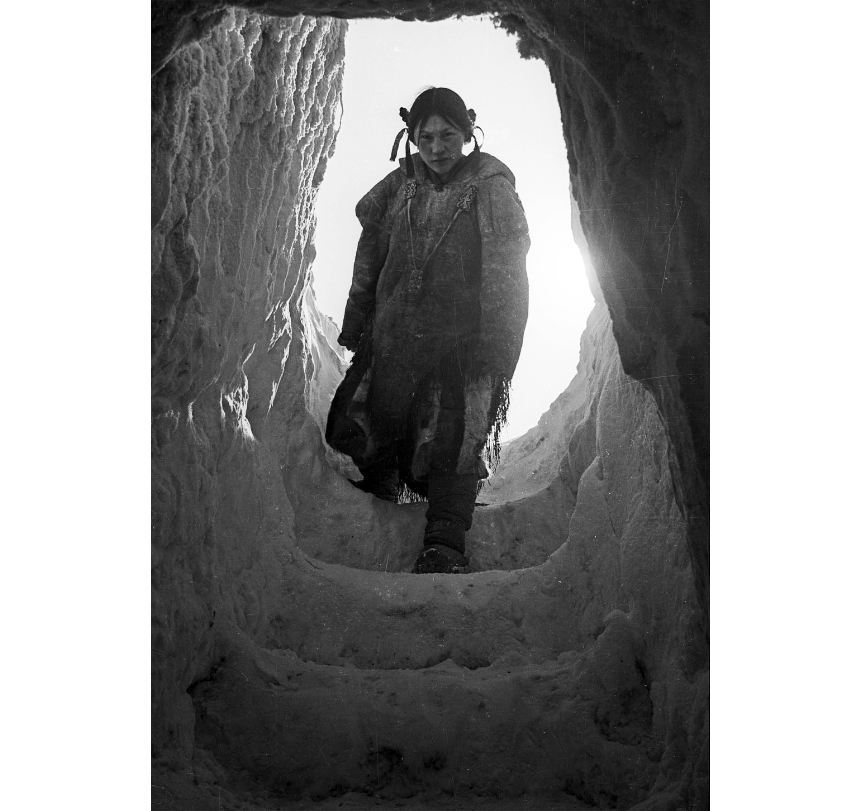

Charles Gimpel, a British photographer and art collector, visited Nunavut a number of times between 1954 and 1968. His guide for many trips out on the land was Quvianatuliak (Kov) Parr, son of artists Parr and Eleeshushe, and an artist in his own right. We have ninety images of Quvianatuliak taken by Mr. Gimpel over the years, mostly of him igloo making. I wanted to honour his contribution to Gimpel’s work by including him here. When most people think of Inuit, an image like this comes to mind. It highlights the global perceptions of Inuit that persist to this day.

This image illustrates that relationship between artists and one of the most prominent figures in the Kinngait (Cape Dorset), NU, printmaking movement, Terry Ryan, the first manager of the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative (now Kinngait Studios). It is also special in that the artists are both women, and they are both parenting and working, bringing their children with them to the print shop. Many female artists across Inuit Nunangat can relate, including myself. Although Library and Archives Canada has many images of famous artists like Kenojuak Ashevak, I thought it would be good to highlight lesser known artists from Kinngait. By some estimates, almost 30% of Kinngait’s population is involved in the arts. Sadly, Petaulassie passed away in her thirties and her work was only included in the 1960 and 1961 Cape Dorset Print Collections.

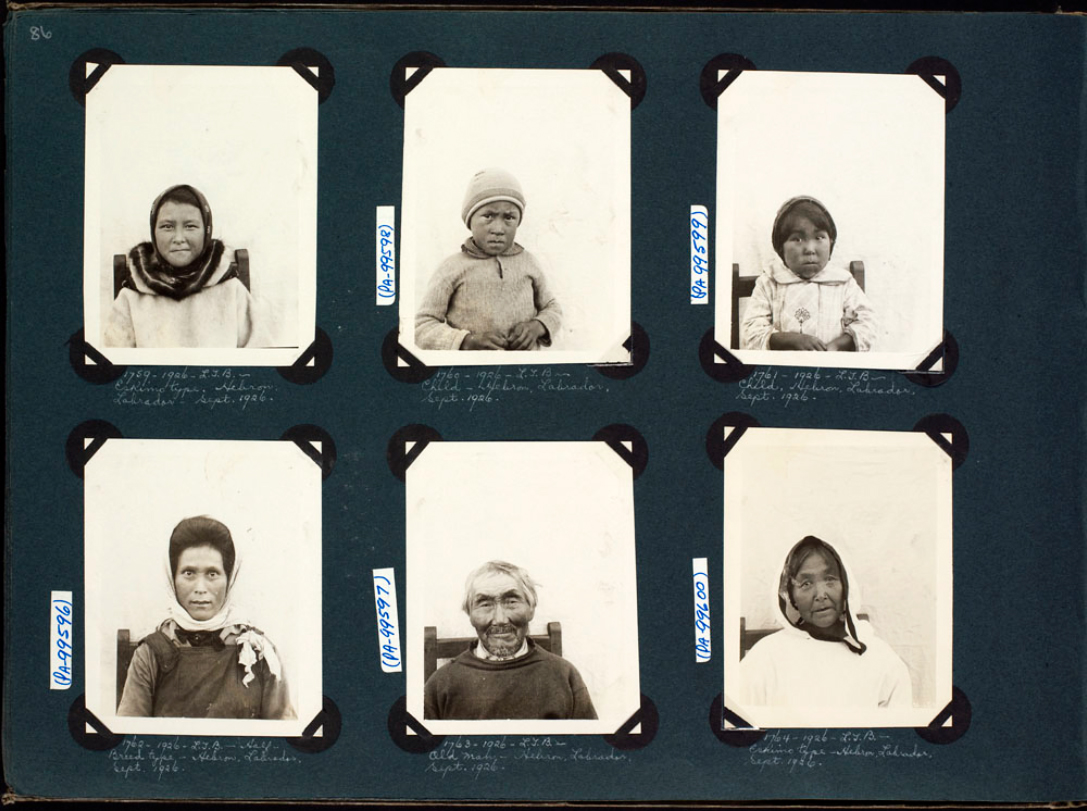

This image struck me many years ago when I first discovered the LAC collection: I had done a simple search for “eskimo” and “Labrador” and this series popped up. I was appalled by the photographer’s classification of people as “eskimo type,” as if these people were zoological specimens. This image inspired a lengthy discussion amongst the We Are Here: Sharing Storiesteam about the words for Inuit in the north or south of Labrador and whether someone is considered mixed race or Inuk. It illustrates how difficult it is to place labels on people from Inuit culture within a colonial context. Each community and each individual is different, and how they identify themselves or each other is different.

Although the description has yet to be changed, we decided she would be called Kablunângajuk as she is from the north coast not the south, and NunatuKavut (those in Southern Labrador) had yet to organize into a politicized group. As part of my research, I read the Nunatsiavut Land Claim section regarding membership, and I contacted a member of the Nunatsiavut membership committee for Rigolet, Nunatsiavut, NL, to ask how they decide on the meaning of Kablunângajuk. It can be used to describe someone of mixed ancestry or someone who could be considered white ethnically, but who was raised as an Inuk with their families having lived in the community for generations.

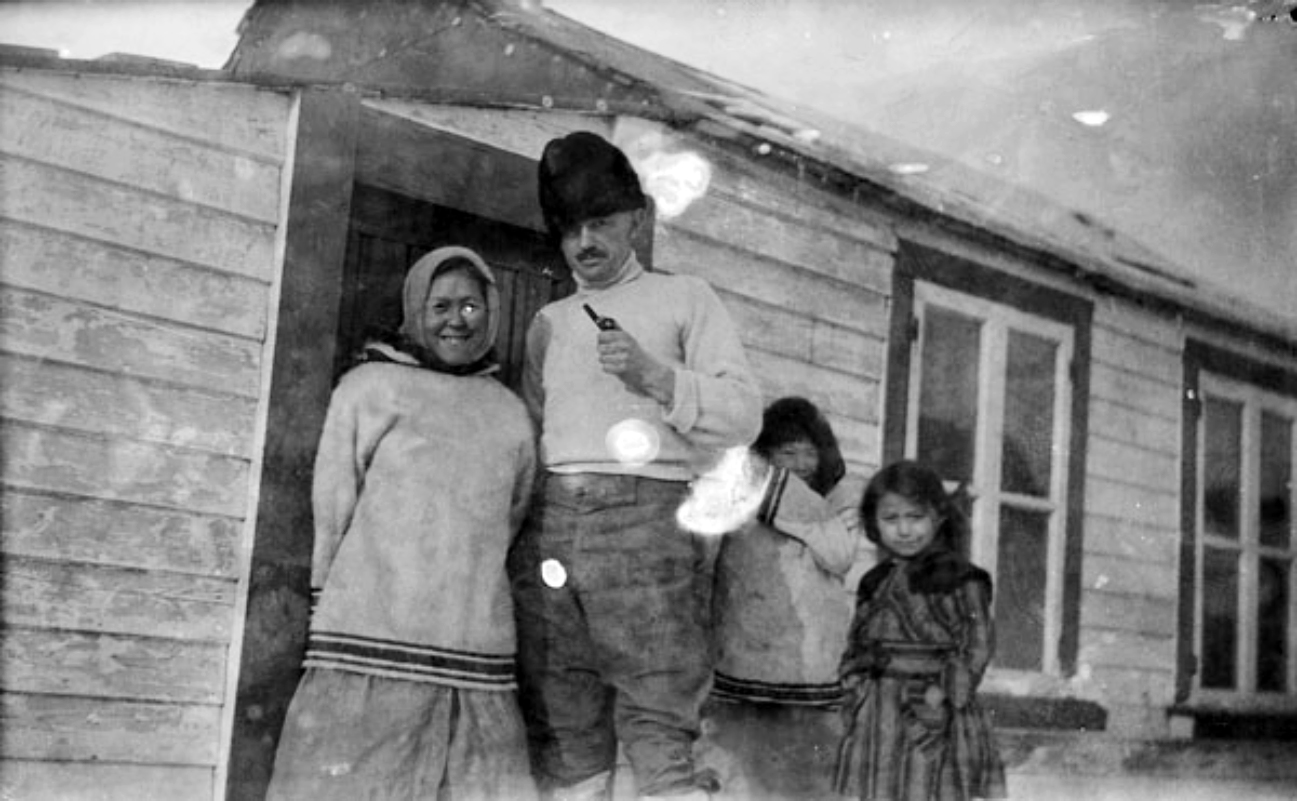

Here we see Judith-Pauline White with her husband Richard White and two of their children. Mrs. White was a photographer who donated her images to researcher Alika Podolinski Webber in 1960 after the death of Mr. White. She took photos mainly of Innu who came to trade at their trading post in Kauk, near Nain, Nunatsiavut, NL. Although Mrs. White was taking photographs at around the same time as Peter Pitseolak, her work was not discovered until we started working on the Podolinski Webber collection.

Gilbert (Bert) Blake was Mina Hubbard’s guide on her celebrated expedition through the Labrador interior to George River in Nunavik, QC, in 1905. Blake was of mixed Inuit and European ancestry, but did not self identify as Inuk. His photograph is a reminder of the relationships between explorers and residents of Inuit Nunangat, as well as the complexities of identity in Nunatsiavut, the most southerly and earliest colonized Inuit region in Canada.

As a result of Project Naming, the two Inuit pictured here are identified (even the man with just one leg showing) but the non-Inuk man is not, a situation which makes me smile, as does Partridge’s natural pose and the warmth in his face. Partridge was a tuberculosis survivor who luckily made it back home and documented his experience in a 1999 Above and Beyondarticle. He became a well known Nunavimmiut radio personality, actor and educator. His daughter is celebrated spoken word poet and artist Taqralik Partridge.

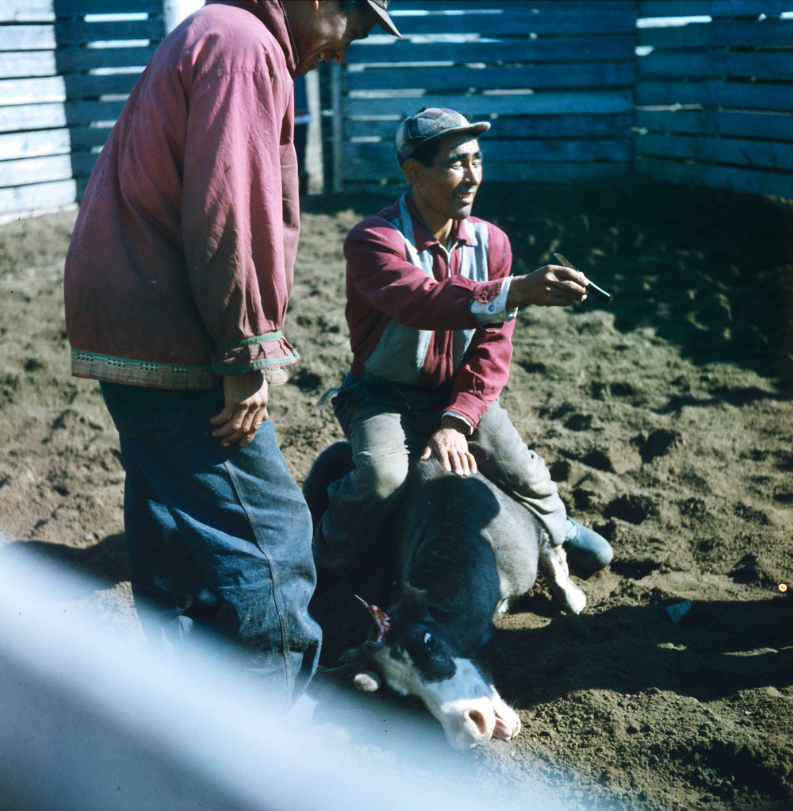

Unfortunately, we were not able to find and digitize much photographic material from the Inuvialuit Settlement Region, but I did come across this image from 1956. The humour and camaraderie were the first things I noticed. This photograph tells the story of an initiative developed in 1925 between Canada and the United States to import reindeer from Alaska and teach people in the Mackenzie Delta area how to herd them. It took five long, arduous years to herd the caribou from Alaska to the North West Territories. Now, the Mackenzie Delta Reindeer Herd is the only free-range herd of reindeer in Canada, consisting of about 3,000 animals.

I hope this collection inspires you to do your own browsing on the Library and Archives Canada site. Through the We Are Here: Sharing Stories Initiative, LAC has digitized over 588,000 pages of texts, maps, rare books, and photographs related to Métis, First Nations, and Inuit. I am sure you will find your own treasures.

NOTES

[1] Heather Campbell has since joined the Inuit Art Foundation team as Strategic Initiatives Director.